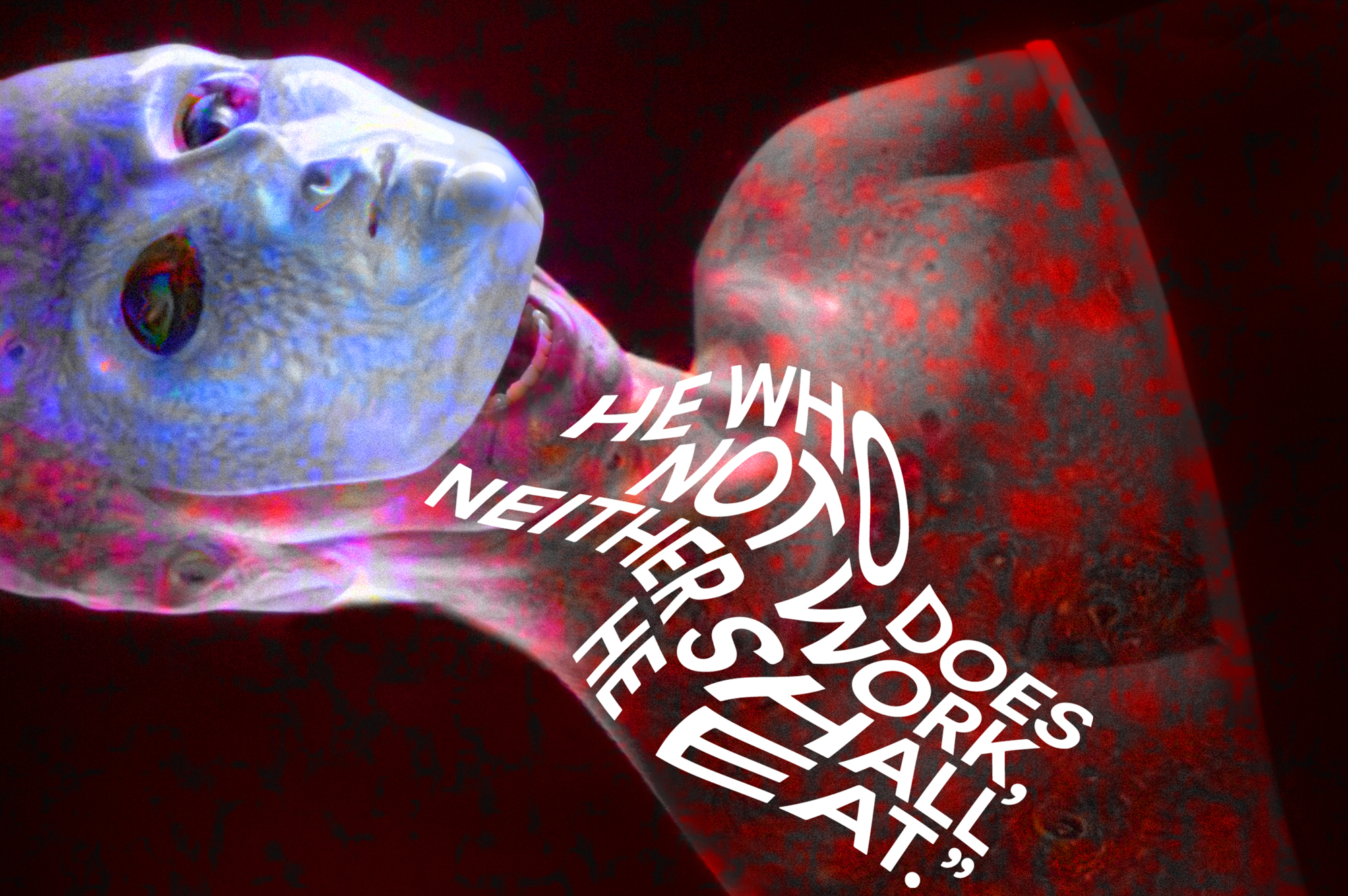

HE WHO DOES NOT EAT

We won’t live to see a post-work world in the same way a factory worker from the 1800s didn’t. Even though the machines these workers operated were the most productive in human history, workers actually worked more hours, not less; workers were forced to pull 10 to 16 hour shifts six days a week in dangerous factories. And while the burden on workers increased, factory owners became fabulously wealthy.

Workers fought back by organizing labor unions; they used slowdowns, strikes, and sabotage to advocate for a fair work-life balance. In turn, the wealthy elite hired private police to suppress workers and lobbied the state to pass anti-union legislation. Because of this, the United States has had perhaps most violent labor history of any industrial nation in the world.⁴ Only after decades of bloodshed were workers afforded the few rights they now have.

The response to this is not to become a Luddite. Good or bad, AI Automation is coming. We must demand and agitate for it to be used in a way that benefits humanity. There have been small, limited actions. For example, several of Google’s software engineers quit their jobs over the company’s agreement to develop AI for the military.⁵ But it will take a much larger organization of both white and blue collar workers to dictate how AI Automation will be utilized. Like the laborers of the past, we must agitate for our rights as workers to be recognized. But what about the workers left behind?

“For the labors of thirty or forty honest and industrious men shall not be consumed to maintain a hundred and fifty idle loiterers,” announced John Smith, governor of the early American Jamestown colony.⁶ But if those 30 or 40 industrious men – aided by AI Automation – could easily provide enough for the rest of the community? Would we soften our distaste for the idle loiterers who have no work, or would we continue demonize them as lazy?

Considering that politicians support slashing benefits and adding work requirements to welfare, the answer more likely the latter. Regardless of how bad the economy gets, there will always be a vocal contingent of people who despise people they consider unfit and lazy. It is vital to the future that we deplatform people who would punish the unemployed and give the underemployed poor a voice. A social transformation must occur, one in which a person is valued not for their productivity but their humanity. Because whether we think it or not, we’re one algorithm away from being a so-called idle loiterer.

The fruits of the Fourth Industrial Revolution must be enjoyed amongst the people, not the hyper-wealthy elite. The only way we can achieve this is by organizing as workers and citizens. The alternative, simply put, is a world of catastrophic inequality.